MILAN – How will COVID-19 affect the coffee market and influence coffee prices? Interkom Spa, a green coffee importer based in Naples, Italy, has sent us this interesting report that were glad to publish. The following document represents one of the first attempts to assess the impact of the coronavirus pandemic on coffee prices.

NAPLES, Italy – The world has changed dramatically in the last three months. A rare disaster, the Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) pandemic, has resulted in a tragically large number of human lives being lost and an ongoing severe global economic recession also known as the Great Lockdown, representing the steepest economic downturn since the Great Depression, and far worse than the Global Financial Crisis in 2009.

The magnitude and speed of collapse in activity that has followed the coronavirus pandemic is unlike anything experienced in our lifetimes, and there is substantial uncertainty about the impact of this crisis on people’s lives and livelihoods.

A lot depends on the epidemiology of the virus, the effectiveness of containment measures, and the development of therapeutics and vaccines, all of which are hard to predict. In addition, many countries now face multiple crises – a health crisis, a financial crisis, and a collapse in commodity prices – which interact in complex ways.

Policymakers are providing unprecedented support to households, firms, and financial markets, and, while this is crucial for a strong recovery, there is considerable uncertainty about what the economic landscape will look like when we emerge from this lockdown.

The following is an analysis of the data provided by the leading international organizations to anticipate the key trends in the coffee supply and demand and give an assessment of the impact of COVID-19 disease on prices of such commodity.

COVID-19 and coffee demand

The recent “International Coffee Organization Coffee Break Series No. 1, April 2020” document tried to provide a preliminary assessment of the demand-side effects of COVID-19, specifically the impact of a global recession on coffee consumption.

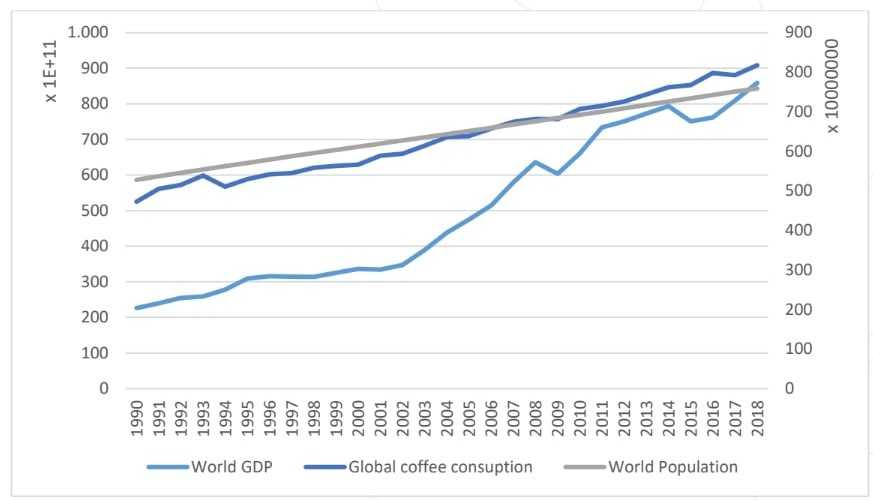

The ICO analysis is based on a sample of the top-20 coffee-consuming countries, representing 71% of global demand, covering the period 1990-2018. The results show that a 1.0% drop in GDP growth is associated with a 0.95% reduction in the growth of global demand for coffee, meaning 1.6 million 60-kg bags.

The ICO analysis has been bitterly contested by various market players. Our analysis as well results a different conclusion, making us believe that the ICO provisions are not correct. Our main critics is the existence itself of a relationship between the GDP and the coffee demand, because of the econometric nature of the latter.

In economics, goods can be separated into two categories according to the time along which they yield utility or are completely consumed: durable and nondurable goods. Food and beverage, such is coffee, are nondurable goods or consumable and, as they allow the consumer to satisfy primary needs, are essential goods in many advanced economies.

Notoriously, the national demand for essential goods is independent of the trend of the national economy. In a recession, consumers continue to buy the same quantity of essential goods, albeit sometimes opting for goods sold at lower prices or for substitutes and complements – as it may be the case of tea, for those consumers living in a traditionally tea-drinking country, such is the United Kingdom.

Provided the role of coffee into advanced economies, we acknowledge as well that its nature may change when considered for emerging market and developing economies, where it may assume a positive income elasticity of demand.

To correctly model an aggregate demand for coffee into any of the main consuming countries, we then considered the development of coffee consumption in relation to the following parameters: population and GDP.

Our dataset was the same one in the ICO report, that is the ICO Global Coffee Database, as well as economic and demographic indicators from the United Nations and the World Bank.

On the other hand, our procedure was significantly different from the ICO one, as we expanded the sample population to the 45 top-consuming countries (instead of 20) representing 96% of global demand, and analyzed the last decade period, being the most statistically relevant.

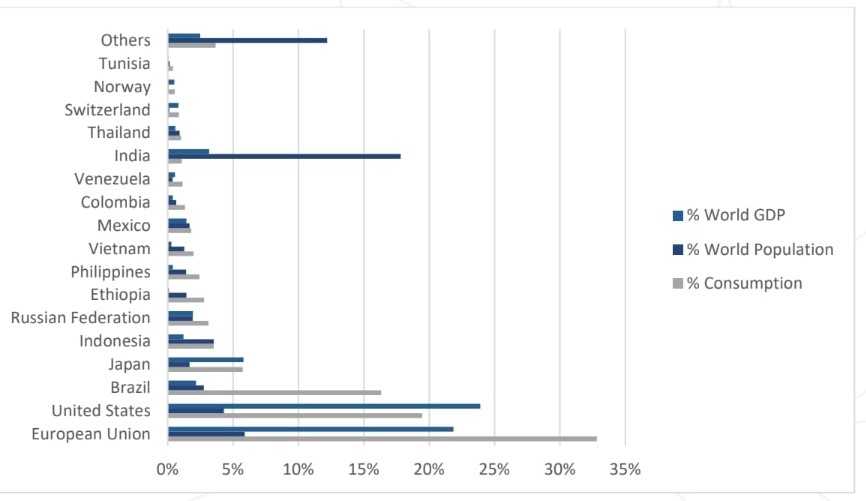

Our sample population of 17 areas accounts for 96% of global coffee consumption, 46% of world population and 65% of world GDP (we considered the European Union as one single area instead of 29 different countries):

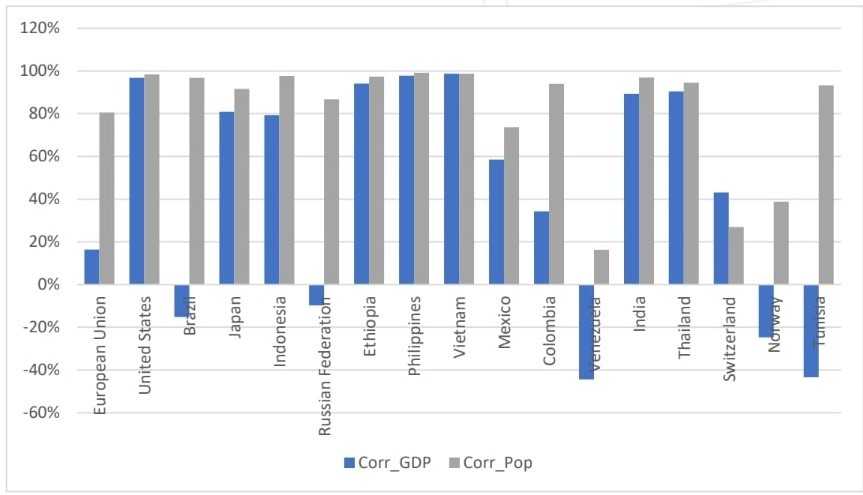

For each area, we calculate the correlation of coffee consumption with both the GDP (Corr_GDP) and the population (Coff_POP) to find the most descriptive one for the trend in consumption:

For each area, we calculate the correlation of coffee consumption with both the GDP (Corr_GDP) and the population (Coff_POP) to find the most descriptive one for the trend in consumption:

In most of the cases (16 out of 17 samples, i.e. 94% of cases), the “population” variable was the most significant one to predict the development of coffee consumption. The conclusion is therefore that it is not realistic to use the GDP as a forecast indicator for coffee consumption, as the analysis of the growth trend into population of the consumer countries is far more significant.

In most of the cases (16 out of 17 samples, i.e. 94% of cases), the “population” variable was the most significant one to predict the development of coffee consumption. The conclusion is therefore that it is not realistic to use the GDP as a forecast indicator for coffee consumption, as the analysis of the growth trend into population of the consumer countries is far more significant.

With the dawn of COVID-19 pandemic, there has been a sustained decline in the out-of-home coffee consumption in favor of the retail segment, but this initial spike in demand does not seems to have the characteristics for a sustained effect, as determined by panic buying and stockpiling more than by real structural motivations.

With the dawn of COVID-19 pandemic, there has been a sustained decline in the out-of-home coffee consumption in favor of the retail segment, but this initial spike in demand does not seems to have the characteristics for a sustained effect, as determined by panic buying and stockpiling more than by real structural motivations.

As well as we do not expect a lower global demand because of the COVID-19 pandemic, as it may seems more plausible a change in consumer behaviors, with an increasing demand for lower-prices blends or brands, and an increasing demand for caffeine substitutes and complements.

COVID-19 and coffee supply

In any market, uncertainty is the main factor of an upward pressure on prices. In coffee market, the highest volatility was recorded when high uncertainty events occurred, such as adverse weather conditions and parasitic infestations, which caused a quick and sudden rise in prices to often unsustainable levels.

The sudden entry of coronavirus added fuel to the fire of a market with strong bullish factors already in the making, such as those rumors in January about Brazil running low on stock for current crop with the risk of postpone current shipments in June when the new crop would have start to reach warehouses.

In this scenario, the concomitant events of the pandemic entered the scene, such as the rapid increase in demand at the beginning of the Great Lockdown and the fear of possible shipment disruptions in some producing countries.

Indeed, the potential points of disruption along the supply chain are many

The global pandemic has prompted governments around the world to impose severe restrictions on people’s movements to stem the spread of the virus.

Supply chains worldwide have sharply slowed down as a consequence of the strains in air, land and maritime transport sectors due to a lack of workforce: therefore, the availability of shipping options has been reduced, and the operations of many seaports are struggling to cope the pace with staff reduced to a minimum.

Furthermore, Europe and United States are short tens of thousands of freight containers, having received only a trickle from China during its coronavirus shutdown at the beginning of the year.

Countrywide shutdowns could limit the migrant workforce that many producers rely upon during harvest season, worsening the shortage of national labor due to coronavirus countermeasures: actually, this scenario would lead to the stop of coffee harvesting operation in those regions like Vietnam and Latin America, where the mechanization of these operations is yet to be extensive.

Luckily, Vietnam and Central America are currently in the off-season and the next harvests are still several months away, while the Arabica crop in Brazil, that is underway in coming weeks, is not entirely but to a large degree mechanized.

Finally, in the long run, the slowdown in shipments and the over-purchasing strategy of many roasters and traders at the beginning of the pandemic could result in a reduction in future purchase commitments, putting the coffee exporters – the real shock absorbers of the supply chain – under financial pressure and cash flow disruptions.

A money shortage that will inevitably increase the credit requirements of the exporters, and they will be forced to pay higher interest rates and rise the prices of coffee to absorb the negative impact of the loans.

In this situation, a negative exchange rate momentum of the national currency against the US dollar, the reference currency for the coffee traded internationally, would potentially lead to a serious financial crisis, which would represent a prelude to the exporters’ default, with a domino effect all along the supply chain up to the importers and the roasters.